Joyce, James

Atherton, James S(tephen) (1910 - ) British Joyce scholar, former lecturer at Wigan District Mining and technical College, Wigan, England, and visiting professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1965. In 1959, Atherton published The Books at the Wake: A Study of Literary allusions in James Joyce's Finnegans Wake, a work he revised and expanded in 1974. The Books at the Wake is a detailed study of the written sources Joyce used when composing Finnegans Wake and of the function these sources play in his wok. It had a seminal impact on Joyce scholarship, providing an important foundation for a range of subsequent studies of the diverse literary influences on Joyce's last work. Atherton also wrote the introduction and notes to the 1965 Heinemann edition of A Portrait of the Author as a Young Man.

Encyclopaedia Britannica,. 1983

James Joyce' abilities

as a novelist and his subtle yet frank portrayal of human nature coupled with

his mastery of language and brilliant development of new literary methods have

made him one of the most commanding influences on the writers of our time. Although

Originally banned in most countries his novel Ulysses describing the

events of a single day June 16, 1904) in Dublin has come to be accepted as a

major masterpiece two of its characters, Leopold Bloom and his wife Molly being

portrayed with a fullness and warmth of humanity unsurpassed in fiction His

Semi- autobiographical novel A Portrait o the Artist as a Young Man is

also remarkable for the intimacy of the readers contact with the central figure

and contains Some astonishingly vivid passages. Dubliners is a collection

of 15 short Stories of Dublin Iife mainly focused upon its sordidness, but the

last, "The Dead," is one of the world's greatest short stories. Critical

opinion is divided over Joyce's last work. Finnegan's Wake, a universal

dream about an Irish family, composed in a multilingual style on many levels

and aiming at a multiplicity of meanings; but although seeming unintelligible

at first reading, the book is full of poetry and wit, containing passages of

great beauty, Joyce other works - some verse (Chamber Music, 1907; Pomes

Penyeach, 1927 Collected Poems, 1936) and a play, Exiles

(1918) - tough competently written, add little to his international stature

..jpg)

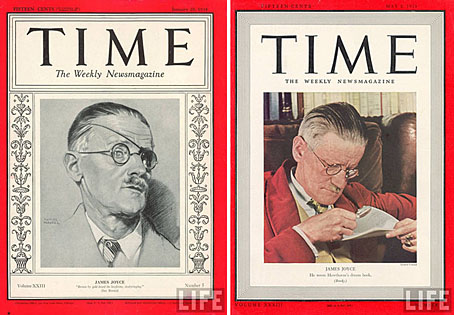

Gisèle Freund, Time Cover, 1939, May 8

Nearly all Joyce's works

are imaginative reconstructions of his own life and early environment and, although

too close an identification of the author with his fictional counterpart can

mislead, a knowledge of his life history helps toward understanding his work.

Early life and work James Augustine Joyce (he rarely used his middle name after

about 1907) was born at Rathagar, Dublin, on February 2, 1882. At that time

the burning question was that of Irish Independence (Home Rule), and the Irish

leader was Charles Stewart Parnell, John Stanislaus Joyce, Jame's father, was

an ardent follower of Parnell, for whom he worked as election agent, an occupation

for which his sociable temperament and ready tongue made him very suitable.

In 1880 he had succeeded in getting two Parnellites returned as members of Parliament

for Dublin and, partly as a reward, had been appointed collector of taxes for

the city at the then considerable salary of £500 a year. Soon after, he

married Mary Jane Murray, from Longford. With his salary, an income of £315

a year from inherited property, and what was left of his grandfather's 21st

birthday present of £1000, the young pair began married life in comfortable

circumstances. James was their eldest son, and when he was six and a half (September

1888), he was sent to Clongowes Wood College, a Jesuit boarding school that

has been described as "the Eton o! Ireland." Such evidence as survives

suggests that he was happy there. But his father was not the man to stay affluent

for long; he drank, neglected his affairs, and borrowed money from his office.

The dividing line came in 1890 - 91 with Parnell's fall following the scandal

over the O'Shea divorce, and in John Joyce's mind the two events were airways

connected. He believed that, with his leader, he has been betrayed and suspected

that the Catholic clergy were somehow responsible. The facts suggest a different

interpretation: he had been absent from his office without permissions while

campaigning for the Parnelite candidates in Cork, and there were deficiencies

in his accounts, which he eventually met by mortgaging his property. The new

Irish Local Government Act had abolished his position, and he was not appointed

to the equivalent one that replaced it, although he vas allowed a pension. His

son James shared his view, and wrote, at the age of nine, a poem attacking T

M. Healy, who, with Michael Davitt, led the Irish opposition to Parnell. The

poem was printed at his father's expense, but no copy is known to, survive.

During the years that followed,

the Joyce family sank deeper and deeper into poverty. Ten children survived

infancy, and they became accustomed to conditions of increasing sordidness,

subject to visits from debt collectors, having household goods frequently in

pawn, and often moving to another house, leaving the rent and tradesmen's bills

unpaid. James did not return to Clongowes after the summer vacation of 1891

but - apart from some months at a Christian Brothers' school, which he never

afterward mentioned - stayed at home for the next two years and, according to

his brother Stanislaus' autobiography, My Brother's Keeper (1958), tried

to educate himself, asking his mother to check his work. In April 1893, both

brothers were admitted, without fees, to Belvedere College, a Jesuit grammar

school in Dublin. James did well there academically and was twice elected president

of the Marian Society, a position virtually that of head boy. He left, however,

under a cloud, as it was thought (correctly) that he had lost his Catholic faith.

He entered University College, Dublin, then staffed by Jesuit priests, although

their control was limited by the Royal University Act of 1879. There he was

taught neither theology nor philosophy. He studied languages, reserving his

energies for extracurricular activities, reading widely - particularly in books

not recommended by the Jesuits - and taking an active part in the college's

literary and Historical Society, Greatly admiring Henrik Ibsen, he learned Dano-Norwegian

to read the original and had an article, "Ibsen's New Drama" - a review

of When We Dead Awaken - published in the London Fortnightly Review

in 1899 just after his 18tjh birthday. This early success confirmed Joyce in

his resolution to become a writer and persuaded his family, friends and teachers

that the resolution was justified. In October 1901 he published an essay, "The

Day of Rabblement" attacking the Irish Literary Theatre (later the Dublin

Abbey Theatre) for catering to popular taste Joyce had previously supported

the theatre and had refused to join a students' protest against the "heresy"

of William Butler Yeats' Countless Cathleen. His next publication was

in the unofficial college magazine, Saint Stephen's, in May 1902. An

essay, "James Clarence Mangan", on an Irish poet who, Joyce claimed,

was unjustly neglected, it was written in an over-elaborate prose and based

on a highly praised lecture he had given to the students' society.

He was leading a dissolute

life at this time but worked sufficiently hard to pass his final examinations,

matriculating with "second class honours in Latin" and obtaining the

degree of B.A. on October 31', 1902. Never did he relax his efforts to master

the art of writing. He wrote verses and experimented with short prose passages

that he called "epiphanies". The word means the manifestations, by

the gods, of their divinities to mortal eyes. But Joyce used it to describe

his accounts of moments when the real truth about some person or object was

revealed. His experiments were useful in helping him to develop a concise style

while recording accurate observation His lifeLong care in preserving g his work,

for future use is first shown in the use He made of his "epiphanies"

in his next two books.

To support himself while writing, he decided to become a doctor, but after attending

a few lectures in Dublin, he borrowed what money he could and went to Paris.

After a fortnight there, during which he found that fees were payable in advance

and his Dublin qualifications insufficient, he returned home for a month's holiday

on December 23, 1902, and became friendly with Oliver St. John Gogarty, whom

he later pilloried as Mulligan in Ulysses. On returning to Paris he abandoned

the idea of medical studies, wrote some book reviews and, on the proceeds of

these and of a few English lessons, with small remittances from his mother,

he studied in the Sainte-Genevieve Library and compiled notes on a theory of

aesthetics he was evolving from Aristotle, Aquinas and Flaubert. The notes and

the book reviews were published in Critical Writings of James Joyce (ed.

E.Mason and R.Ellmann, a1959)

Recalled home in April 1903 because his mother was dying, he tried various occupations, including teaching and lived at various addresses, including (from September 9-19, 1904) the Martello Tower at Sandycove, now Ireland's Joyce Museum. He had begun writing a lengthy naturalistic novel, Stephen Hero, based on the events of his own life, when in 1904 George Russell (AE) offered £1 each for some simple short stories with an Irish background to appear in a farmers' magazine, The Irish Homestead. In response Joyce began writing the stories published as Dubliners (1914). Three stories, "The Sisters," "Eveline," and "After the Race," had appeared under the pseudonym Stephen Daedalus before the editor decided that Joyce's work was not suitable for his readers. Meanwhile Joyce had met, on June 10, a girl named Nora Barnacle. He met her next on June 16, the day that, mainly in celebration of their meeting, he chose as what is known as "Bloomsday" (the day of his novel Ulysses). On June 16 he fell in love with her, and eventually persuaded her to leave Ireland with him, although he refused, on principle, to go through a ceremony of marriage.

Trieste - 1905 Joyce

and Nora left Dublin together in October 1904. Joyce obtained a position in

the Berlitz School, Pola, working in his spare time at his novel and short stories.

In 1905 they moved to Trieste, where James's brother Stanislaus joined them

and where their children, George and Lucia, were born. In 1907, while giving

English lessons to a Triestine businessman, Ettore Schimitz, he learned that

Schimitz had written under the name Italo Svevo but had become discouraged.

Joyce admired his work and exerted influence to obtain recognition for it. In

1906-07, for eight months, he worked at a bank in Rome, disliking almost everything

he saw. Ireland seemed pleasant by contrast; he wrote to Stanislaus that he

had not given credit in his stories to the Irish virtue of hospitality and began

to plan a new story "The Dead." The early stories were meant, he said,

to show the paralysis form which Dublin suffered, but they are written with

a vividness that arises from his success in making every word and every detail

significant. His studies in European literature had interested him in both the

Symbolists and the Realists; his work began to show a synthesis of these two

rival movements. He decided that Stephen Hero lacked artistic control

and form and rewrote it as "a work in five chapters" under a title

- A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man - intended to direct attention

to its focus upon the central figure. In Trieste, too, Joyce wrote, but never

tried to publish, a poetical short story, Giacomo Joyce, describing his feelings

toward one of his pupils Amalia Popper, whose father was named Leopoldo and

whose Jewish charms contributed to the character of Molly Bloom. The manuscript,

found among Stanislaus' papers, was edited and published with a foreword by

Richard Ellmann in 1968.

In 1909 he visited Ireland twice to try publish Dubliners and set up

a chain or Irish cinemas. Neither effort succeeded and he was distressed when

a former friend told him that he had shared Nora's affections in the summer

of 1904. Another old friend proved this to be a lie. Joyce's reactions can still

be read in a series of letters now in the Cornell University Library. Only the

milder passages could b e published in the "collected" Letters

of James Joyce; the series as a whole includes some of the most astonishing

examples of erotica ever written. Joyce always felt that he had been betrayed

and the theme of betrayal runs through much of his later work. So, almost equally,

does that of tenderness. "The Dead" mentions a boy named Michael Furey

who dies for love of the heroine, Greta. He is based on a boy called Michael

Bodkin, who had once courted Nora. On his next and final visit to Ireland in

1912, Joyce visited "the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey

lay buried", and he brought its "crocked crosses" into the closing

cadences of his story. But printers' objections to the themes, to the frequent

mention of real places and people, and to occasional use of the word bloody

prevented the publication of Dubliners till 1914, by which time A

Portrait of the Artist was being serialized in The Egoist (a review financed

by Harriet Shaw Weaver). Both publications were favourably reviewed.

Zurich - 1915. When Italy declared war in 1915 Stanislaus was interned, but James and his family were allowed to go to Zurich. At first, while he gave private lessons in English and worked on the early chapters of Ulysses - which he had first thought of as another short story about a "Mr. Hunter" - his financial difficulties were great. He was helped first by a grant of £75 from the Royal Literary Fund; then by a large grant from Mrs. Edith Rockefeller McCormick; and finally by a series of grants from Miss Weaver, which by 1930 amounted to more than £23000. Her generosity resulted partly from her admiration for his work and partly from her sympathy with his difficulties, for, as well as poverty, he had to contend with eye diseases that never really left him. From February 1917 until 1930 he endured a series of 25 operations for iritis, glaucoma, and cataracts, sometimes being for short intervals totally blind. Despite this he kept up his spirits and continued working, some of his gayest passages being composed when his health was at its worst. Unable to find an English printer willing to set up A Portrait of the Artist for book publication, Miss Weaver published it herself, having the sheets printed in the United States where it was also published, on December, 29, 1916, by B W Huebsch, in advance of the English Egoist Pres edition . Encouraged by the acclaim given to this, in March 1918, the American Little Review began to publish episodes from Ulysses, continuing until the work was banned in December 1920.

Paris - 1920 After World War I Joyce returned for a few months to Trieste, then - at the invitation of Ezra Pound - in July 1920 he went to Paris. Ulysses was published there on February 2, 1922, by Sylvia Beach, proprietor of a bookshop called "Shakespeare & Co". The book, already well known because of the censorship troubles, became immediately famous. Joyce had prepared for its critical reception by having a lecture given by Valery Larbaud who pointed out the Homeric correspondences in it and that "each episode deals with a particular art or science, contains a particular symbol, represents a special organ of the human body, has its particular colour… proper technique, and takes place at a particular time."

Joyce never published this scheme (See table); indeed he even deleted the chapter titles in the book as printed. It may be that this scheme was more useful to Joyce when he was writing that it is to the reader. Sometimes the technical devices become too prominent, particularly in the much praised "Oxen of the Sun" chapter (11, 11) where the language goes through every stage in the development of English prose from Anglo-Saxon to the present day to symbolize the growth of a fetus in the womb. The execution is brilliant, but the process itself seems ill-advised. More often the effect is to add intensity and depths, as, for example, in the "Aeolus" chapter (II, 4) set in a newspaper office, with rhetoric as the "art" Joyce inserted into it hundreds of rhetorical figures and many references to winds - something "blows up" instead of happening, people "raised by the wind" when they are getting money and the reader becomes aware of an unusual liveliness in the very texture of the prose. The famous last chapter, in which we follow the stream of consciousness of Molly Bloom as she lies in bed, gains much of its effect from being written in eight huge unpunctuated paragraphs. Nevertheless, the main strength of the book lies in its depth of character portrayal and its breadth of humour. Joyce claimed to have taken his "stream-of-consciousness" technique from a forgotten French writer, Edouard Dujardin (1861-1949), who had used the monologue intérieure in his novel Les Lauriers son coupés (1888), but many critics have pointed out that it is at least as old as the novel, although no one before Joyce had used it so continuously.

In Paris Joyce worked on Finnegan's Wake, the title of which was kept secret, the novel being known simply as "work in Progress" until published in its entirety in May 1939. In addition to his chronic eye troubles Joyce suffered great and prolonged anxiety over his daughter's mental health. What had seemed slight eccentricity grew into unmistakable and sometimes violent mental disorder that Joyce tried by every possible means to cure, but it became necessary to place her in a mental hospital near Paris. In 1931 he and Nora visited London, where they were married, his scruples having yielded to his daughter's complaints.

Meanwhile he wrote and rewrote sections of his new book; often a passage was revised more than 14 times before he was satisfied. Every word, every letter was scrutinized and pondered over. He usually began with a simple narrative. Basically the book is, in one sense, the story of a publican in Chapelizod, near Dublin, his wife, and their three children; but Mr. Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, Mrs., Anna Livia Plurabelle, Shem, Saun and Isabel are every family of mankind, the archetypal family about whom all mankind is dreaming. The 18th century Italian Giambattista Vico provides the basic theory that history is cyclic; to demonstrate this the book begins with the end of a sentence left unfinished on the last page. Ideally it should be bound in a circle. It is thousands of dreams in one. Languages merge: Anna Livia has "vlossy-hair"- wlossy being Polish for "hair"; "a bad of wind" blows; bad being Turkish for "wind." Characters from literature and history appear and merge and disappear as "the intermisunderstanding minds of the anticollaborators" dream on. On another level, the protagonists are the city of Dublin and the River Liffey which flows enchantingly through the pages, "leaning with the sloothering slide of her, giddygaddy, grannyma, gossipaceous Anna Livia." An throughout the book James Joyce himself is present, joking, mocking his critics, defending his theories, remembering his father, enjoying himself.

Despite much scholarly study the book remains imperfectly understood; Joyce said he expected his readers to spend their lives on his book. It will remain a book for the minority, but it will always be loved by that minority. Since its publication it has had a great effect on many serious writers, as well as providing a new technique of word distortion and word creation for writers of advertisements.

After the fall of France

in World War II (1940), Joyce took his family back to Zurich, where he died

on January 13, 1941, still disappointed with the reception given to his last

book. He would be pleased to know that, of the two periodicals now dealing with

his work, one is entirely devoted to Finnegan's Wake.

Major Works

Novels and Stories:

Dubliners (1914), 15 short stories; "The sisters", An Encounter,"

"Araby", "Eveline", " After the Race,""Two

Gallants,""The Boarding House," "A Little Cloud," "Counterparts,"

"Clay," "A Painful Case," " Ivy Day in the Committee

Room," "A Mother," " Grace" and "The Dead";

A Portrait o the Artist as a Young Man (1916), Ulysses (1922),

Finnegan's Wake (1939), sections published as parts of Work in Progress

from 1928 to 1937.

Verse: Chamber Music (1937); Pomes Penyeach (1927); Collected

Poems (1936)

Play: Exiles

(1918)

Bibliography:

The definitive biography,

Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (1959), is reliable and exhaustive. Critical

studies of the works are very numerous; a list to December 1961 is given in

R H Deming.

A Bibliography of James Joyce Studies (1964). The most concise account

is A.Walton Litz, James Joyce (1966), which contains a well selected

bibliography with helpful comments. H. Blamires, The Bloomsday Book (1966),

is the best single guide for anyone reading Ulysses for the first time. Frank

Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses, new ed. (1960) gives an

intimate account of Joyce at work. For the earlier works Marvin Magalaner, Time

of Apprenticeship (1959); and a collection of essays, James Joyce's Dubliners

(1969) contain useful material; and R.Choles and K M Kain, The Workshop of

Daedalus (1965) reprints Joyce's Epiphanies and the Pola and Trieste

notebooks. No fully satisfactory account of Finnegan's Wake has yet been

written. W Y Tindall, A Reader's Guide to Finnegan's Wake (1969),

is the most up-to-date comprehensive study but is not always reliable; Adaline

Glasheen, A Second Census of Finnegan's Wake (1963), provides necessary

identifications. The James Joyce Quarterly (1963- ) gives regular surveys

of current critical work; A Wake Newsletter (1962- ) now published by

English Department of Dundee University, Scotland, continues explicating Finnegan's

Wake.