ESSAY

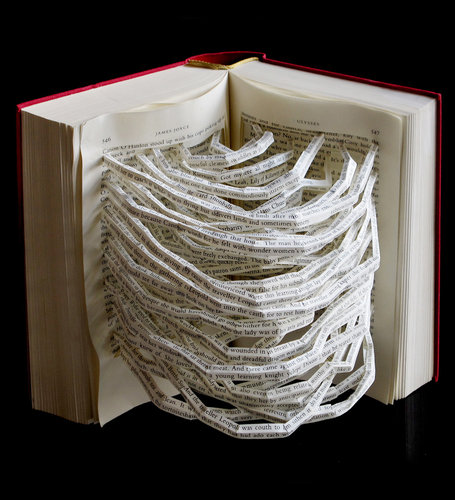

Reasons to Re-Joyce

By DARIN STRAUSS

Published: December 7, 2012

The information has gone wide, it’s a note pushed under every reader’s door: Literary fiction is in serious trouble. That’s the deal, The Huffington Post told us so. (You know articles that bewail the consensus even as they work to create it? Well, this HuffPo story had the title “The Death of Literary Fiction?” — and that question mark was only a prop from the “You still beat your wife?” store of weighted questions.) There have been other slights. Here’s how The Millions worded theirs: “The good ship Literary Fiction has run aground.” And don’t get me started on David Shields’s 2010 he-man fiction-haters’ manifesto, “Reality Hunger.”

Now, it would be one thing if the naysayers were talking about a crash dive of sales figures. Sales figures carry the inarguability of math. But these people are talking about something a little more hazy. Remember, we’re living in the year of the Awardus Horribilis, the Pulitzer Debacle. The prize committee checked out every American novel on offer, shrugged and went galumphing offstage. That was, without a doubt, a verdict on quality.

So things might look pretty bad. But to me, the scurrilousness has the pasty complexion of po-faced error. The worry, the criticism, feels tacky and fatuous. Just this season I happened to read, back to back to back, new and oddly similar masterpieces. And I mean, legitimate masterpieces. I think the naysaying misses not only the fact that this has been a wildly good book year but also the emergence of a new trend. It’s less a school or a movement than a clutch of writers who share a really unlikely pedigree: “Ulysses.”

I’m talking about Zadie Smith’s new novel, “NW”; “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk,” by Ben Fountain; and Michael Chabon’s “Telegraph Avenue.” Each of these novels is guided not by some contemporary light but by, of all things, James Joyce’s maximalist standard. Of the three, as far as I can tell, only “NW” has been cited by critics as outright indebted to “Ulysses.” The knots that tie Smith to Joyce are (as one reviewer has it) her “syntactic and structural tortuousness,” her “blink-and-you-might-miss-it obliqueness,” or (as many other reviewers have it) her “stream-of-consciousness style.” And it’s the Joycean stuff that critics have objected to: the “verbal gimmicks” (The New Republic) of this “confusing” book that “doesn’t bother with much of a plot” (Entertainment Weekly, grade: B).

Yes, what some reviewers find confusing is Smith’s taking up Joyce’s famous difficulty. But it is also her adoption of Joyce’s restless desire to portray things boldly and freshly, to crumple the tissue between thought and experience and toss it away for good. Or at least, for the good of the story. Watch how Smith bends or strips away punctuation here, and somehow conveys what Isaiah Berlin referred to as the specific flavor, the “exact quality of a feeling”:

“Pass the heirloom tomato salad. The thing about Islam. Let me tell you about Islam. The thing about the trouble with Islam. Everyone is suddenly an expert on Islam. But what do you think, Samhita, yeah what do you think, Samhita, what’s your take on this? Samhita, the copyright lawyer.”

Eu, Roque, pergunto, what is your take on that:

The scene is one of contemporary fiction’s tableaux vivants. It puts modern life’s bumps and zones almost within touch.

I should mention that Smith is, like me, a professor at New York University. I should further mention that this type of writing is not unprecedented. It uses a Joycean technique, free indirect discourse, that treats the mishmash of place and person like a kind of flux transfer event. But “NW” doesn’t sound like “Ulysses.” Or rather, its impressive mind both sounds like “Ulysses” and doesn’t: mostly, it sounds like the present, like an intensified right now.

As for verbal gimmicks? Forgive anything from a novelist who describes a woman’s bellybutton as “a tight knot flush with her stomach, a button sewn in a divan.”

When you come across a Joycean note like this, you realize how few sing it, especially lately. Faulkner, Gaddis, Colum McCann — only a handful have made personal music of the influence. Some of our most talented authors poke at “Ulysses.” Richard Ford: “Overrated . . . hands down.” Walter Kirn: “James Joyce was unintelligible, even to my professors.” Elizabeth Gilbert: “By Page 10, as always, I’m like, ‘What the hell . . . ?’ ”

But Michael Chabon has clearly read “Ulysses,” and he’s made his own best novel by using the same totem that so irked these others. “Ulysses” is the favorite book of a main character’s father. And the Joycean influence dares Chabon to greatness. “Telegraph Avenue” is a different masterwork from “NW” — more crowd-pleasing, the Irish inheritance happily married to what V. S. Pritchett called “the American bounce.” It’s fun — “Ulysses” as filmed by Tarantino — and stacked with more allusions than “The Waste Land.” But it references pop in place of classical culture; rather than “Tristan und Isolde” and “The Canterbury Tales,” Chabon writes of Luke Cage and Sly Stone. (How great a loss you find this depends on who you are.)

As ever, Chabon is a performing magician. He can take any topic and stage it so the crowd smiles and even oohs its amazement. (A pure impenetrable, like Gaddis, can also reach into the hat but no entertainment comes out twitching its whiskers.) And in “Telegraph Avenue,” it’s not just the extraordinary spoon-bending prose. The author is made bigger by the range and sublimity of his model.

This is a book of wordplay and bravado — one chapter is made up of a single long sentence, and the opening page’s “Moonfaced, mountainous, moderately stoned, Archy Stallings manned the front counter of Brokeland Records, holding a random baby” owes its movement to Joyce’s “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather.” But what is most reminiscent here of “Ulysses,” and of “NW,” is that Chabon makes a grab for the entire world in a single, bighearted book.

“Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk” is a succès d’estime, the only book here nominated so far for a major literary prize, in this case, a National Book Award. Though in keeping with the novel-bashing trend, its reception in the press has been too muted. In Commentary magazine, D. G. Myers called the nominees “the Worst National Book Award list since the Last National Book Award list.”

Superficial affinities with “Ulysses” can be found in the textual capers Fountain cuts. To soldiers on leave from the Iraq war, overused phrases — “terrRist,” “nina leven,” “currj” — atomize into word fog, letters typeset across empty pages, meaningless. More substantially, like Joyce, Fountain lays his hand over a day and place (Texas Stadium, Thanksgiving, 2004) and takes an entire country’s temperature.

Each of these maximalist novels shows an ease with big-ticket issues: race and fame, personal and civic responsibility, how to maintain a sense of self in an overwhelmed society. The surprise is that such ease isn’t more infrequent. But in recent fact, there’s been a long line of excitedly received maximalist novels (“Super Sad True Love Story,” “Swamplandia!,” “The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet”) and less-than-maximalist novels (“Freedom,” “The Marriage Plot”), and so perhaps it’s not that implausible to see three great books in one season. The touchdown-to-fumble ratio seems better lately than in the Roth-Updike-Bellow-dominated ’70s, say, or in the D.F.W.-Lorrie Moore-DeLillo-dominated ’90s.

I am not happy writing this. I am a novelist; I experience the books discussed here as thrown gauntlets, as loogies hawked right onto my shoes. But who knows? Maybe good novels beget more good novels. Think of all the track stars who chugged right up behind Roger Bannister’s sub-four-minute mile; think of Sonny Rollins taking a Williamsburg Bridge sabbatical to keep up with Coltrane. No: think of all those rabbits, just waiting to peek out from inside all those hats.

Darin Strauss’s most recent book, the memoir “Half a Life,” won

a National Book Critics Circle Award.

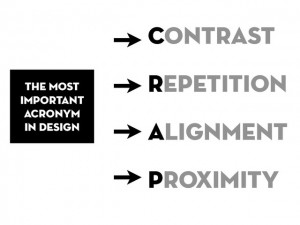

Expressando visualmente: (Roque)

Você projeta (design) assim e diz que é assim

O que é mesmo, é CRAP...