James Joyce

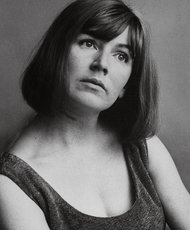

By

EDNA O'BRIEN

A Lipper/Viking Book

Once Upon a Time

* * *

0nce upon a time there was a man coming down a road in Dublin and he gave himself

the name of Dedalus the sorcerer, constructor of labyrinths and maker of wings

for Icarus who flew so close to the sun that he fell, as the apostolic Dubliner

James Joyce would fall deep into a world of words—from the "epiphanies"

of youth to the epistomadologies of later years.

James Joyce, poor joist, a funnominal man, supporting a gay house in a slum of despond. His name derived from the Latin and meant joy but at times he thought himself otherwise—a jejune Jesuit spurning Christ's terrene body, a lecher, a Christian brother in luxuriousness, a Joyce of all trades, a bullock-befriending bard, a peerless mummer, a priestified kinchite, a quill-frocked friar, a timoneer, a pool-beg flasher and a man with the gift of the Irish majuscule script.

A man of profligate tastes and blatant inconsistencies, afraid of dogs and thunder yet able to strike fear and subordination into those he met; a man who at thirty-nine would weep because of not having had a large family of his own yet cursed the society and the Church for whom his mother like so many Irish mothers was a "cracked vessel for childbearing." In all she bore sixteen children; some died in infancy, others in their early years, leaving her and her husband with a family of ten to provide for.

"Those haunted inkpots" Joyce called his childhood homes, the twelve or thirteen addresses as their financial fates took a tumble. First there was relative comfort and even traces of semigrandeur. His mother, Miss May Murray, daughter of a Dublin wine merchant, versed in singing, dancing, deportment and politeness, was a deeply religious girl and a lifelong member of the Sodality of Our Lady. She was a singer in the church choir where her future and Rabelaisian husband John, ten years her senior, took a shine to her and set about courting her. His mother objected, regarding the Murrays as being of a lower order, but he was determined in his suit and even moved to the same street so as to be able to take her for walks. Courtships in Dublin were just that, through the foggy streets under the yellowed lamps, along the canal or out to the seashore which James Joyce was to immortalize in his prose—"Cold light on sea, on sand on boulders" and the speech of water slipping and slopping in the cups of rock. His father and mother had walked where he would walk as a young man, drifter and dreamer, who would in his fiction delineate each footstep, each bird call, each oval of sand wet or dry, the seaweed emerald and olive, set them down in a mirage of language that was at once real and transubstantiating and would forever be known as Joyce's Dublin. His pride in this was such that he said if the Dublin of his time were to be destroyed it could be reconstructed from his works.

James Augustine Joyce was their second son, born February 2, 1882. An infant, John, had died at birth, causing John Joyce to indulge in a bit of bathos, saying, "My life was buried with him." May Joyce said nothing; deference to her husband was native to her, that and a fatality about life's vicissitudes. John Joyce's life was not buried with his first son; he was a lively, lusty man and for many years his spirit and his humor prevailed. But sixteen pregnancies later, and almost as many house moves, impecunity, disappointments and children's deaths did make for a broken household. His enmity toward his wife's family and sometimes toward his wife herself was vented at all hours—the name Murray stank in his nostrils whereas the name Joyce imparted "a perfumed tipsy sensation." Only the Joyce ancestry appeared in photographs and the Joyce coat of arms was on proud display. He was a gifted man, a great tenor, a great raconteur and one whose wit masked a desperate savagery.

James, when young, was known as "Sunny Jim" and being a favorite he would steal out of the nursery and come down the stairs shouting gleefully, "I'm here, I'm here." By the time he was five he was singing at their Sunday musical parties and accompanying his parents to recitals in the Bray Boat Club. By then too he was wearing glasses because of being nearsighted. That he loved his mother then is abundantly clear, identifying her with the Virgin Mary, steeped as he was in the ritual and precepts of the Catholic Church. She was such a pious woman that she trusted her confessor more than any member of her own family. She was possessive of Sunny Jim, warning him not to mix with rough boys and even disapproving of a valentine note which a young girl, Eileen Vance, had sent to him when he was six:

O Jimmie Joyce you are my darling

You are my looking glass from night till morning

I'd rather have you without one farthing

Than Harry Newall and his ass and garden.

His mother with her "nicer smell than his father" was the object of his accumuled tenderness and when he was parting from her he pretended not to see the tears under her veil.

Jesuits

* * *

The grim stone Castle of Clongowes Wood College was where he was enrolled at

the age of "half past six." His father wanting the finest education

for his little prodigy sent him to the Jesuits, where older boys "ragged"

him as to whether he had kissed his mother before he fell asleep. Admitting

to it, he saw his mistake and henceforth denied it. The Jesuits he called in

his adult life a "heartless order that bears the name of Jesus by antiphrasis."

Yet his indoctrination from them he thought invaluable. A photograph the day

he left home shows James in Little Lord Fauntleroy outfit, kneeling by his mother,

who was flanked by her husband and her father, two men inimicable to one another,

John Joyce calling the father "the old fornicator" because he had

been married twice and the father observing his quiet daughter becoming worn

down with a pregnancy each year, infants to nurse and siblings to take care

of.

Soon the reports were that James spent more time in the infirmary than in the classroom and to make his yearning all the worse he suffered an injustice which he never forgot and never forgave. Forgiveness was anathema to him. A boy had snatched his glasses and stood on them but a priest believed that Joyce had done it himself to avoid lessons and gave him a "pandying." He did not show his tears in public but at night he wept, fearing that he would die before his mother came to get him. He wrote a hymn to the two mothers, the earthly and the celestial one. As an altar boy, the ritual and liturgy of the Catholic Church engendered a kind of ecstasy in him and the Virgin Mother in her tower of ivory was the creature he adored. Church had all the pageantry of theater until he became aware of the scarifying sermons which inhuman prelates boomed out, gloating in their versions of punishment and their seething visions of hell. He absorbed it all, remembered it all and transcribed it into the languid and lacerating autobiographical novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. But the fear was so ingrained in him that he used to envisage death creeping from his extremities, in the same way as Socrates had observed the flow of the hemlock, the bright centers of the brain extinguished one by one, just like lamps, the soul's confrontation with God and then the designation for all time—heaven, purgatory or hell.

His stay there lasted just over three years and he left abruptly through lack of funds. So it was home to an even smaller house, where for months he tutored himself, wrote poetry and began a novel which has vanished without trace; the stint with the Christian Brothers and then to Belvedere College, another Jesuit school—"a Jesuit for life, a Jesuit for diplomacy" as he put it. But already from the mother he so loved he was distancing himself. When making his confirmation at Clongowes and being allowed to choose a saint's name he chose Aloysius, the saint who, in imitation of Pascal, would not allow his mother to embrace him because he feared contact with women. In his new school James excelled at lessons and won prizes for the best English compositions. The money helped to buy clothes and food for the needy family and even allowed for little trips to the theater. It was supposed that he would be a priest; so devout was he that he would stay on after Mass to have his private deliberations with God. His mother would boil rice especially for him because of his studiousness. When the family went picnicking to Howth or the Bull Wall at Clontarf he would bring little notebooks with summaries of history or literature, lists of French and Latin words, and while the other children swam he would set himself tests and get his mother to examine him. The priests who taught him recognized that he had a plethora of ideas in his head, one priest predicting that "Gussie" would be a writer.

The transition he underwent in just a few years has all the determination of a Samurai. He went from childlike tenderness to a scathing indifference, from craven piety to doubt and rebellion. His first sexual arousal happened when he was twelve and walking home with a young nurse who told him to turn away while she urinated. The sound of this was an excitement to him. A year later he was stopped by a prostitute and the wavering faith was soon to be quenched forever as he realized that he could not lead a life of sinlessness or celibacy. First it was covert, his life at home and at school one thing, his inner life quite another as he began to question the tenets of Church and family. Before long he went to the brothels and a fascination for these forbidden houses remained with him all his life. He viewed them to be the most interesting places in any city. He wrote about them in Ulysses and endowed them with a thrilling hallucinatory life that was hardly true of the seedy dungeons which he frequented. The girls he had met earlier, those vestals with whom he had played charades at Christmas parties, were prim and hypocritical—no match for one who had determined "to sin with another who would exult with him in that sin."

The Jesuits began to notice this laxity and questioned Stanislaus whose role in life was that of a beleaguered younger brother, "as useful as an umbrella." Unnerved by their questioning of him, Stanislaus let it slip that James had a habit of romping in the bedroom with a young maid and so Mrs. Joyce was summoned. She dismissed the maid and warned the neighbors of the girl's transgression. Chastity at all costs and this in a house with only three bedrooms, eight or nine children, further conceivings and a father who came home drunk, irate and boisterous. "Bridebed, childbed, bed of death, ghostcandled"—the young James was witness to it all.

After the death of yet another child, Frederick, the desperate father tried to strangle the mother, seized her by the throat, shouting, "Now by God is the time to finish it." As bedlam broke out, with younger children in terror, James knocked his father to the floor and pinioned him there while his mother escaped to a neighbor's house. A few days later a police sergeant called to give the father a severe talking—to and while the beatings might have stopped, the threats and the shouting went on. For John Joyce, finding no outlets for his wayward gifts, his frustration had to be vented on his family. Walking across Capel Street Bridge half drunk one night, escorted by the young James, he decided that the boy needed a formative experience and held him upside down in the Liffey for several minutes. Yet no wrong done by that father wrankled because they were both "sinners."

(C) 1999 Edna O'Brien All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-670-88230-5